Dominic CascianiHome and Legal Correspondent

Dominic CascianiHome and Legal Correspondent BBC

BBCLast week Kemi Badenoch announced that the Conservative Party would take the UK out of the European Convention of Human Rights if they won the next election.

“I have not come to this decision lightly,” the Tory leader said. “But it is clear that it is necessary to protect our borders, our veterans, and our citizens.”

Her words came on the eve of the party’s annual conference, at a time when the Conservatives are under enormous pressure from Reform UK.

Nigel Farage’s party also wants out of the ECHR, as well as other international treaties that he thinks stand in the way of curbing illegal immigration. Liberal Democrat leader Sir Ed Davey, meanwhile, has been just as strident the other way.

“Kemi Badenoch has chosen to back Nigel Farage and join Vladimir Putin,” he declared – adding “this will do nothing to stop the boats or fix our broken immigration system”.

EPA

EPAPrime Minister Sir Keir Starmer has weighed in, though he hovers somewhere in between. He told the BBC he does not want to “tear down” human rights laws, but backs changing how international law is interpreted to stop unsuccessful asylum seekers blocking their deportation.

But while strongly-worded opinions over whether or not to pull out of the treaty make for easy headlines, the consequences are deeply complicated. Even Badenoch acknowledged last year that leaving would not be a “silver bullet” for tackling immigration.

So how is it that such a nuanced issue has been reduced to a political hot potato?

Dodging political bullets

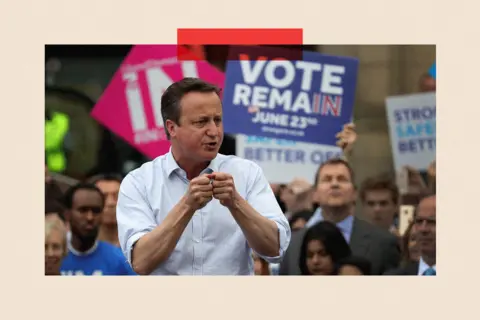

It was back in 2011 – not far into David Cameron’s tenure as prime minister – that this issue came to the forefront of domestic politics.

It centred around the case of John Hirst, a man convicted of manslaughter, who argued the UK’s blanket ban on prisoners voting in any circumstances was a breach of human rights. In 2005 Strasbourg had ruled in his favour. It essentially said the UK’s policy was too black and white.

Cameron’s Labour predecessors Tony Blair and Gordon Brown dodged the political bullet of being seen to give in to the court.

But when the relatively new Tory PM said he felt “physically ill” at the prospect of giving jailed criminals the vote, his soundbite propelled the ECHR to the heart of public consciousness.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe ECHR had been largely drafted by a British team and aimed to impose on post-fascist Europe a “never-again” package of legal rights.

Its content drew heavily on historic laws – for example the concept of Habeas Corpus (banning unlawful detention), can be seen in the ECHR’s Article 5.

Officially, the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg polices those rights. And when it rules that a country is in breach, the member states come together to find a way of fixing the problem in the Council of Europe (nothing to do with the EU).

But in the UK, there is also the Human Rights Act, which means ECHR cases can be dealt with by its own judges.

Disputes between UK courts and Strasbourg can be worked through too – what happened following the John Hirst case is testament to this.

In 2017, ministers allowed offenders who had been released on licence the right to vote – but made clear that Parliament would never allow votes for criminals still in prison cells. The Council of Europe closed the case. And just weeks ago the Strasbourg court threw out a fresh attempt by a prisoner to re-open the issue.

Yet it was the original clash, together with Cameron’s comments in 2011, that stuck in many minds.

PA Media

PA MediaAdding fuel to the fire that same year, Theresa May – home secretary at the time – shared a story during party conference about a Bolivian man who avoided deportation because of his pet cat.

This illustrated the problem with human rights laws, she argued.

Only the story, as May told it, wasn’t entirely correct, according to England’s top judges.

The Home Office indeed wanted to send the man home as an illegal immigrant. And the cat – called Maya – had featured in the man’s appeal. But that was only a tiny part of the detailed evidence he provided.

A spokesperson for the Judicial Office at the Royal Courts of Justice, which issues statements on behalf of senior judges, said at the time that the cat was “nothing to do with” the eventual judgement, which allowed the man to stay.

Yet the pet became a source of unintentional humour – and when a judge cracked a joke about the cat no longer needing to fear adapting to Bolivian mice, the case took on a life of its own.

By that autumn, a mood had begun to take hold about human rights that, 14 years later, has culminated in the Conservatives pledging to leave the ECHR.

‘Open-ended and obscure obligations’

Richard Ekins KC, a professor at the University of Oxford, is a staunch critic of the ECHR on the basis that membership in his view compromises UK sovereignty.

“But there is a more fundamental problem,” he argues. “And the fundamental problem can be observed by paying attention to what the court has been doing, which really is quite openly to expand the Convention’s reach over time.”

He references a case last year, where the court ruled that Switzerland had breached human rights by failing to tackle climate change.

The incredibly complex judgement was celebrated by campaigners as a game-changer – but a British judge, Tim Eicke KC, said the majority on the panel had “gone beyond what it is legitimate and permissible for this court to do”.

Getty Images

Getty Images“The judgment… imposes very far reaching, but also open ended and obscure obligations on member states,” argues Prof Ekins.

“Domestic courts are going to be invited to apply the European Court’s new approach to discipline, supervise [and] control climate policy, which obviously is a highly complicated and tangled set of considerations that intersect with social policy, economic policy, foreign policy.”

This is the heart of his argument: a court completely divorced from the political will of the British people is now making the UK do things that are far beyond its original remit.

“It’s incompatible – its intention at least – with parliamentary democracy,” he argues.

Hijacked by the immigration debate

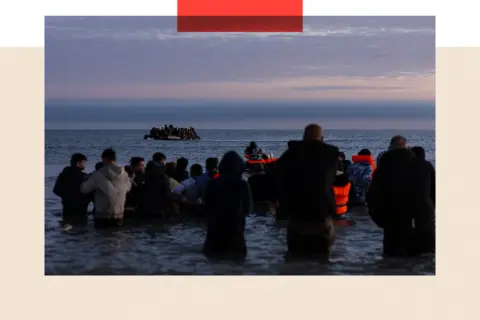

Nowhere is the allegation of overreach stronger in British politics than in Reform’s claim that the ECHR is to blame for problems with the UK’s migration system.

Yet the evidence supporting this claim is often anecdotal and complex – as was the case with Maya the cat.

A study of media stories about the ECHR by the University of Oxford’s Bonavero Institute for Human Rights found that fewer than 1% of all foreign criminals who have appealed against their deportation in the UK have won their case on human rights grounds.

When cases went as far as Strasbourg, the court tended to throw them out.

PA Media

PA MediaThat’s not to say there are no issues at all.

Lord Jonathan Sumption, the former Supreme Court judge, believes that some decisions by immigration tribunal judges have become “extravagant” and far removed from the original boundaries of the right to family life.

“I have no problem about the text of the Convention,” he says. “I do have a problem about the unlimited expansion which it’s undergone at the hands of the Strasbourg Court.

“It’s unfortunate that the whole issue has been hijacked by the question of immigration.

“I think that it will make some difference to the ability to keep people out or deport them if we are not members of the ECHR. But I think the extent that it will make a difference is not widely understood – and has been greatly exaggerated.”

Would leaving the ECHR ‘stop the boats’?

So, would leaving the ECHR really “stop the boats”, to use Rishi Sunak’s phrase?

“The number one problem about deporting illegal immigrants, first of all, is finding a place which will take them and which is not unsafe,” argues Lord Sumption.

“And secondly, [there is] the Refugee Convention. It doesn’t require us to take in asylum seekers. It does require us to adjudicate on their claims and give them certain rights once they’ve got here, even if they got here illegally.

“The ECHR is certainly an additional difficulty, but not as great a difficulty, as is suggested.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe UK government has already promised to devise clearer and stricter rules that will tell immigration officials and judges how to interpret the right to family life.

“I think it is a runner,” argues Sir Jonathan Jones, who was the Treasury Solicitor until 2020. This, he believes, could be the best way forward – particularly around the definition of the ECHR’s Article 8, which guarantees the right to, among other things, family life.

“It’s legitimate for the government to say we will take a tighter view, as a proper, reasoned, good faith attempt to rein in what we think Article 8 covers and what it doesn’t.”

But Alex Chalk, the last Conservative Lord Chancellor before Labour won power, argues that the UK government needs to seek reform faster.

“The ECHR is not holy writ,” he told the BBC during the Conservative party conference. “This government should be moving much more quickly to seek urgent reform. [It] should have been saying, look, we want to lead on this to do this in six weeks.

“The US Constitution was drafted in 15 weeks or so. This really can be done.”

‘Rights are going to suffer’

Human rights lawyer Harriet Wistrich is concerned about what could be lost if the UK does leave the ECHR. It has, she argues, been at the forefront of challenging the state’s treatment of victims of awful abuses.

“We were able to hold Greater Manchester Police accountable on behalf of Rochdale grooming gang victims through civil [damages] proceedings.

“The Hillsborough inquests were possible by having Article 2 [the right to life] inquiries into deaths, where you want to examine what went wrong and what the state could have done differently.

“If we withdraw fully… it’s those rights that are going to suffer,” says Ms Wistrich, who is also the founder of the Centre for Women’s Justice.

EPA

EPABeyond legal battles at home, there are big international questions too around leaving.

The 1998 Belfast Agreement, the cornerstone of peace in Northern Ireland, and the post-Brexit deal with the European Union placed respect for human rights law at their centre. Critics of withdrawing from the EHCR predict both could come crashing down.

But Professor Ekins believes that you can have human rights safeguards without a supranational court overseeing all nations.

He and colleagues wrote a detailed proposal on Northern Ireland that argue the historic arrangements don’t require the UK to remain in the ECHR, providing it honours human rights and cross-community power-sharing arrangements by other means.

James Manning/PA Wire

James Manning/PA WireThe issues in Northern Ireland and the Republic could, however, go deeper. Sir Jonathan Jones for one is sceptical about how leaving the ECHR would go down in both places – because the ECHR’s role in the agreement was to demonstrate to a lot of people who do not trust the British state that there are laws in place to protect them.

“The thing about the Convention is that it constrains governments, and it constrains the way that governments can treat minorities and people it doesn’t like,” he says.

“If we were out of the ECHR, you wouldn’t have that constraint.”

Alex Chalk warns there could be an international price to leaving, too. There is value, he says, in sitting at the Council of Europe and raising issues with French and German counterparts at international conferences.

“You should try to reform before you yank your way out because inevitably there could be cost to doing so,” he argues.

But ultimately, he adds, “this is a matter of politics more than it is of law”.

Top image: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.