Guy DelauneyBalkans correspondent

Guy Delauney/BBC

Guy Delauney/BBCAn impasse over Russian oil and imminent US sanctions has put Serbia at loggerheads with its traditional ally in Moscow.

Added differences over Russian gas supplies and Serbia’s arms trade have ramped up the tensions, with Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic trading barbs with the Kremlin.

The root of the problem, and the most pressing issue, is the fate of Serbia’s national oil company.

Russia’s Gazprom and Gazprom Neft own more than half the shares of Petroleum Industry of Serbia (NIS). That has put the company in a tight spot, after US sanctions on NIS came into effect last month over its ties to Russia’s energy industry.

Serbian Energy Minister Dubravka Djedovic Handanovic has told the BBC that NIS’s Russian owners have now asked the US for a waiver, which indicated “the Russian side was ready to transfer the control and influence upon the company to a third party”. But she warns time is running out.

The impact of US sanctions on NIS has been immediate.

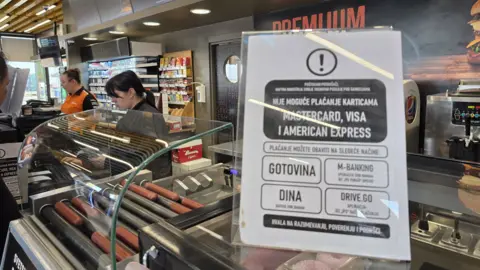

Its petrol stations have put up signs warning customers that Visa and Mastercard can no longer be used to pay for fuel, as the US credit card giants have stopped processing payments.

The same applies to outlets of NIS’s Russian shareholders. At a Gazprom service station on the motorway between Novi Sad and Belgrade, Bojan and his colleagues were taking no chances, pumping the petrol and diesel for their customers.

That gave them the opportunity to check whether the drivers had the means to pay, and Bojan said about one in 10 customers did not – “mostly foreigners”. A cash machine has been installed inside the service station just in case.

Guy Delauney/BBC

Guy Delauney/BBCNIS operates both of Serbia’s oil refineries, providing more than four-fifths of its petrol and diesel, and almost all its jet and heavy fuels.

Serbia is landlocked, so it relies on Croatia to deliver oil via its Janaf pipeline. But since sanctions kicked in, the flow has been cut off.

The refineries will run out of crude to process before the end of November, which is why the energy minister says time is running out.

Serbia is not the only Balkan country grappling with US sanctions.

Neighbouring Bulgaria has passed legislation to take over its only oil refinery from Russian oil giant Lukoil, ahead of sanctions kicking in on 21 November.

Hungary’s Viktor Orban has secured a one-year waiver from his ally President Donald Trump.

At the start of November a queue of NIS tankers could be seen waiting for entry to the jet fuel storage facilities at Belgrade’s Nikola Tesla Airport, delivering supplies while they still could.

National airline Air Serbia told the BBC that it was “adjusting [its] business activities” and had taken “the necessary steps” to ensure it could keep its planes in the air.

Russia’s shareholders have not been in a rush to sell their stakes in NIS, even though Belgrade says they are now prepared to act.

Nationalisation would be another possibility, as in Bulgaria, but Serbia has been reluctant to follow suit, in large part due to its longstanding friendship with Russia.

Unlike its neighbours it is not part of the EU, which has banned imports of Russian oil, although it is a candidate to join.

Alexander Zemlianichenko/Pool via REUTERS

Alexander Zemlianichenko/Pool via REUTERSThe episode has undoubtedly strained relations with Moscow. Behind the scenes, there is a great deal of exasperation in Serbian government circles.

The energy minister chose her words carefully, but her frustration was clear.

“The overall income in the Gazprom group of NIS is insignificant,” Dubravka Djedovic Handanovic told the BBC.

“We know NIS is not crucial for Russia’s energy sector and contributing significantly to any income for the Russian government. However, for Serbia it is very important.”

“These [US] sanctions will harm Serbian people, because of the majority share that NIS has in the market. NIS employs 13,500 people in Serbia, so employees are important for us as well as stability in the market.”

Oil is not the only problem.

Serbia also relies on Russian gas, delivered at a highly favourable rate. But the current supply deal expires at the end of the year – and Moscow seems in no rush to renew, leaving President Vucic “very disappointed”.

“It is obvious we didn’t get the gas agreement because there is a possibility that we could nationalise NIS,” says Zeljko Markovic, a Serbian energy sector consultant.

“We can supply Serbia without Russian gas, but the question is at what price? We have been using Russian gas at a lower than market price. And are we prepared with the contracts and the capacities?”

Arms and ammunition exports have also soured relations with Russia. Serbia’s defence companies have not supplied Ukraine directly, but they have made deliveries to third countries which then re-exported the munitions.

Earlier this year, Moscow made it clear this was no longer acceptable – and President Vucic imposed an export embargo. But at the end of last month he changed tack, saying he was happy for Serbia to export arms and ammunition to EU countries, adding that the buyers could “do what they want” with the deliveries.

This triggered a testy exchange between Russia’s foreign ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova and Vucic.

There are signs of movement.

If the bid for a US waiver works, then the sanctions will be lifted, and oil will start flowing to NIS’s refineries again.

But there is still no sign of a gas deal – and the extent of the damage to Serbian-Russian relations may be significant.

Vucic often insists that Serbia’s path leads towards the European Union. If nothing else, this episode may strengthen that conviction.