Dominic CascianiHome and legal correspondent

Reuters

ReutersFor 20 years the Home Office has been blighted with regular and well-documented failures to manage asylum seekers.

Home Secretary Shabana Mahmood’s massive plan is unprecedented. And the legal and policy strategy marks an enormous change in thinking.

In short, the government wants to move from thinking about “duties” the Home Office must fulfil to what “powers” it really needs to take and use to get a grip on the situation.

Given ministers want to do this without demolishing constitutional safeguards such as the Human Rights Act, it is a tightrope.

At the heart of this plan – which sits alongside the slowly evolving “smash the gangs” project – is a massive reform of what refugee status leads to.

At the moment, anyone accepted for protection is basically here for life, if they choose.

Future applicants will enter a temporary system of safety called “Core Protection”.

A refugee would get a minimum 30 months of permission to live in the UK before it is reviewed. Putting aside the logistical question of how the Home Office will find the resources to constantly check up on people, the aim is to encourage people to go home if conditions improve. How that works in practice as people get jobs and their children grow up with the UK their only secure home, is not clear.

But even if their homeland remains unstable, a refugee will not be allowed to permanently settle for 20 years – unless they “earn” a short cut through work or study.

On top of that, the government wants to cut financial support to asylum seekers (currently £49 per week) if they hold eligibility to work. That’s about 20,000 people. Others will be told to sell assets to pay for their upkeep – although officials are trying to avoid the PR optics of the controversial Danish policy of taking jewellery off people.

Families who have been rejected for asylum may ultimately lose their financial support to encourage them to leave.

But laws applying in all parts of the UK are absolutely explicit that a child cannot be left “in need”. It’s just a no-go zone for the government. So how removing support from an asylum family squares with that cornerstone safeguard remains to be seen.

At the moment there are about 700 Albanian families in the UK with no right to be here but the Home Office has chosen not to prioritise sending them home. Past plans to remove asylum families have been really knotty – and it was a huge point of tension within the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition of 15 years ago.

The next stage of the plan – and this will not happen overnight – is to change how asylum decisions are taken.

Officials who have studied the Danish system say they are planning a similar single appeal system that can speed up the whole process and be fairer.

But past attempts at asylum “fast track” decision-making have been torn apart in the courts because they were rushed and found to be grossly unfair.

If the Home Office is going to get it right this time, it will require an astonishing amount of focus that has eluded it before.

The plan to impose on British courts a tight interpretation of the right to family life, Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, is a key ingredient of the package. The aim is to show that the UK can maintain human rights safeguards that are baked into our messy constitution while also ending immigration abuse.

Evidence of abuse of human rights laws in the courts is not immediately apparent. We are still waiting for the Home Office to come up with some detailed statistics on how rights like family life are used in legal challenges.

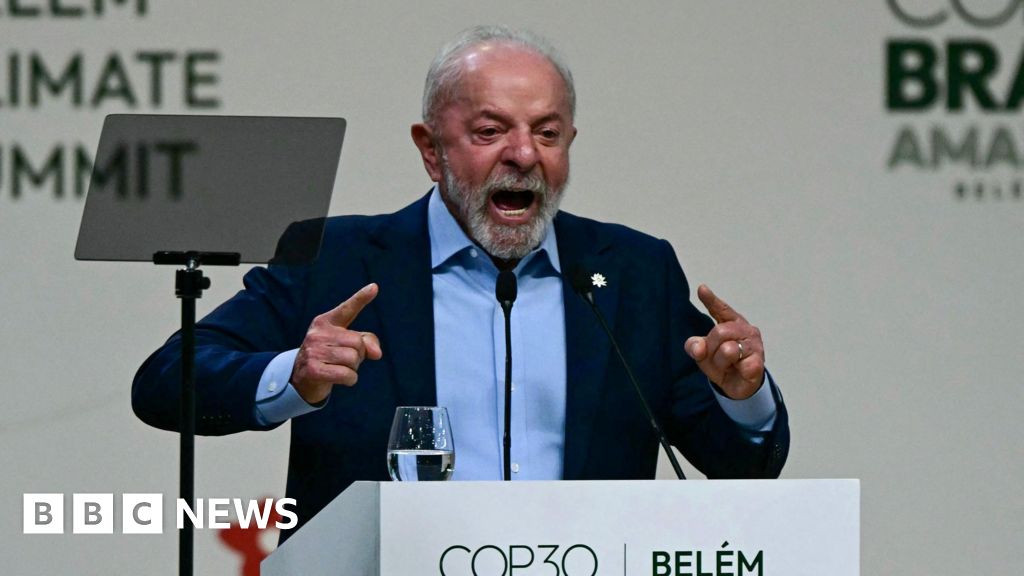

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesBut, nevertheless, Parliament will be asked to approve wording for how judges should balance the right to a private and family life and the public interest in removing someone from the UK.

What makes a family? Well the government plans to legally restrict the definition to “immediate” family.

All of this will need to be watertight to prevent a clash with the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg where complaints might be lodged that the UK has gone too far.

Such a clash is not a given. The court must take into account local circumstances and the UK rarely loses at the court, and almost never on immigration related issues.

All of this is going to take time to get right and there are two massive warnings from history if ministers get it wrong.

The first is the Windrush scandal. So far, the Home Office has coughed up more than £116m in compensation to people whose lives were turned upside down by being wrongly labelled as illegal immigrants under the former government’s “hostile environment” policies.

The second warning? There have been times in European history when the public has lost confidence in how society works – and turned to strong men with easy and angry answers.

The risk today, believe ministers, is the illegal immigration problem has been so poorly managed, for so long, that British traditions and values of offering protection to the truly vulnerable are in danger.

One government insider said this may be the last chance for mainstream politicians to grip this problem and solve it.