Suranjana TewariAsia Business Correspondent

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen Prabowo Subianto campaigned to become Indonesia’s new president, he promised dynamic economic growth and major social change.

But his first year in office has not lived up to this populist platform. Rather, his ambitious pledges have been confronted by the realities of South East Asia’s biggest economy.

A frustrated youth, worried about jobs, took to the streets in late August to protest against the rising cost of living, corruption and inequality – the government was forced to roll back the perks for politicians that had triggered public fury. There had been huge protests earlier in the year too, against budget cuts that hit healthcare and education spending.

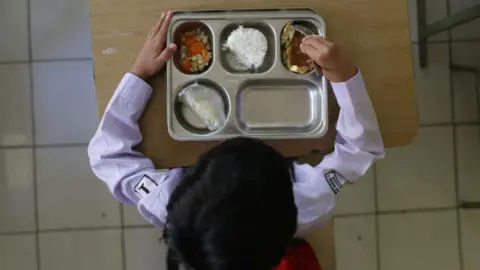

What didn’t help was that this coincided with an expensive free school meals programme – at an annual cost of $28bn (£20.8bn). A centrepiece of Prabowo’s agenda, it aims to tackle child malnutrition, improve education outcomes and stimulate the economy. Officials describe it as “an investment in Indonesia’s future.”

Except, in recent months images have emerged showing weak, dehydrated children – some as young as seven – hooked up to intravenous drips. They were suffering from food poisoning after eating the free lunches

With more than 9,000 children falling ill since the scheme was rolled out in January, critics are questioning whether it’s delivering at all, or straining public resources while racking up debt.

Analysts warn all of these challenges highlight broader issues in public spending and oversight – and those, in turn, point to deeper strains in Indonesia’s $1.4tn economy.

Discontent on the streets

It is a critical time for the vast archipelago of more than 280 million people, spread across thousands of islands.

Despite steady annual growth of roughly 5% in recent years, Indonesia is feeling the pressure of slowing global demand, rising living costs and competition from regional neighbours like Vietnam and Malaysia. Both of those countries have successfully attracted foreign companies trying to diversify production away from China.

The protests in August, which left 10 people dead, captured the extent of public anger over Prabowo’s government. Demonstrators accused it of prioritising prestige policies and projects over providing economic support.

Prabowo – who has set an ambitious growth target of 8% by 2029 – and his ministers continue to defend their policies, saying they will create jobs and stimulate demand.

“We have an experience of growing beyond 7%. So… Indonesia knows that higher growth is achievable. But of course, we have to see the global economics and the global trade,” Indonesia’s Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs Airlangga Hartarto told the BBC.

Experts say that achieving such growth will require careful management of public finances and foreign investment.

A new sovereign wealth fund, Danantara, which is targeting high-impact projects across renewable energy and advanced manufacturing could spur higher growth, said Adam Samdin from advisory firm Oxford Economics.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAirlangga told the BBC that Indonesia is “ready” and willing to “spend on the right sector of the economy”.

But ambitious and challenging commitments like the free school meals programme make some question Prabowo’s priorities. Some health-focused non-governmental organisations are urging him to stop the scheme.

He defended it last month, saying “Brazil needed 11 years to reach 47 million beneficiaries. We’ve reached 30 million in 11 months. We’re quite proud of what we’ve achieved.”

Another example is India, which has the world’s biggest school lunch programme, feeding nearly 120 million students.

But unlike in Brazil and India, the Indonesian programme has been accused of being ineffective, despite its much higher cost, because of the mass food poisonings.

Indonesia faces unique challenges. It doesn’t have the infrastructure for safe and speedy meal delivery to schools across its 6,000 inhabited islands, Mr Samdin said.

That includes proper refrigeration transport, as well as strict food safety standards and resources to enforce them to keep food fresh in the tropical heat.

So the government is relying on third parties and contractors for the programme, which makes it even harder to monitor quality.

But a flagship programme that is faltering is not Prabowo’s only challenge.

The search for investment

US President Donald Trump’s trade war has not spared Indonesia, which now faces 19% tariffs on exports to America.

Airlangga, who was involved in the negotiations, said he was grateful for a tariff rate that could compete with rivals like Thailand, Malaysia and the Philippines, and that he expected the US-Indonesia trade deal to be signed by the end of October.

But 19% is still a high cost for exporters who will also face pressure from Chinese goods being redirected to Asia to avoid high tariffs in Europe and the US.

Indonesia – which is on the search for new markets and partners – also signed a trade deal last month with the European Union, which it had been negotiating for almost 10 years. Airlangga expects trade with the bloc to increase by two and a half times over the next five years.

But investment, which has spurred manufacturing and created jobs in countries like Thailand and Vietnam, has become a challenge here.

Foreign companies have long complained of red tape and the cost of doing business in Indonesia, but they still came because of the large consumer base and resources. It is flush with nickel and copper, which are integral to electric vehicles and other green technology, and palm oil.

But these were not industries that required huge manpower, which meant they never created jobs on the same scale as manufacturing did in countries like China and Vietnam.

Airlangga said Indonesia is now investing in the digital economy to create more jobs and boost growth. But whether it can provide enough people with the right skills to staff data centres and other such ventures is the big question.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesData centres also require investment and investors are especially rattled after the abrupt sacking of the highly respected former finance minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati.

Mulyani’s house was ransacked in the protests by demonstrators, who blamed her for the high cost of living. Her replacement is a relatively unknown official, Purbaya Yudhi Sadewa, who has said the protests were due to monetary “mistakes”.

He is a big supporter of Prabowo’s ambition for 8% annual growth by 2029 – a rate the country has not achieved since the 1990s.

Even the current 5% rate of expansion is disputed by some economists, who also say economic data has been politicised to meet Prabowo’s growth target. Airlangga denied this.

“I’m optimistic that Indonesia is still attractive,” he said, citing “the value chain, the investment climate and the quickness of President Prabowo to do deregulations”.

Economists, however, say falling car sales, shrinking foreign investment, contraction in manufacturing and reports of layoffs suggest economic activity is weakening, rather than strengthening.

“Indonesia’s economy is based on consumption, and so from the perspective it can continue to provide a steady engine even if it does not grow significantly,” Mr Samdin said.

“Growth might slow, but the sheer size of the population will provide some economic activity.”

That may reassure optimistic investors but it does not solve the challenges that lie ahead for President Prabowo.