Premier Li Qiang contextualised the agreement in light of “greater development challenges” facing Asean nations, as they are “unfairly subjected to steep tariffs”, an indirect criticism of the erratic measures unleashed across the region by US President Donald Trump.

Another noteworthy moment at the summit was the formal accession of East Timor, a prominent economic and trade partner of China, Indonesia and Singapore.

On the surface, Sino-Asean relations have never looked more promising. Asean has been China’s primary trading partner since 2020, with bilateral trade surging from US$160 billion in 2006 to almost US$1 trillion in 2024. Chinese investments in infrastructure – from railways to ports and gas pipelines to energy grids – have played an instrumental role across both the continental Asean states of Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos as well as maritime nations such as Indonesia and Malaysia.

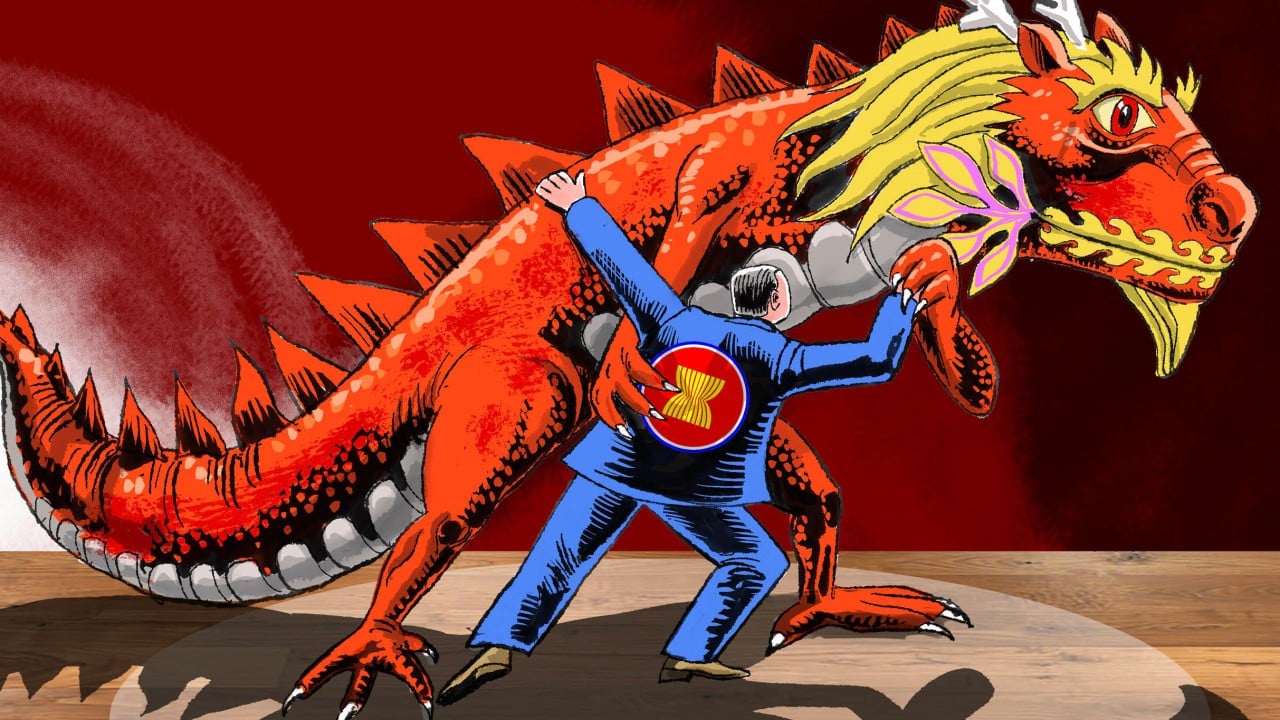

However, the reality is more complex. When I speak to policymakers, business elites and young students in Asean countries, the rise of China comes across as a double-edged sword.