How would you behave if your democracy was being dismantled? In most western countries, that used to be an academic question. Societies where this process had happened, such as Germany in the 1930s, seemed increasingly distant. The contrasting ways that people reacted to authoritarianism and autocracy, both politically and in their everyday lives, while darkly fascinating and important to study and remember, seemed of diminishing relevance to now.

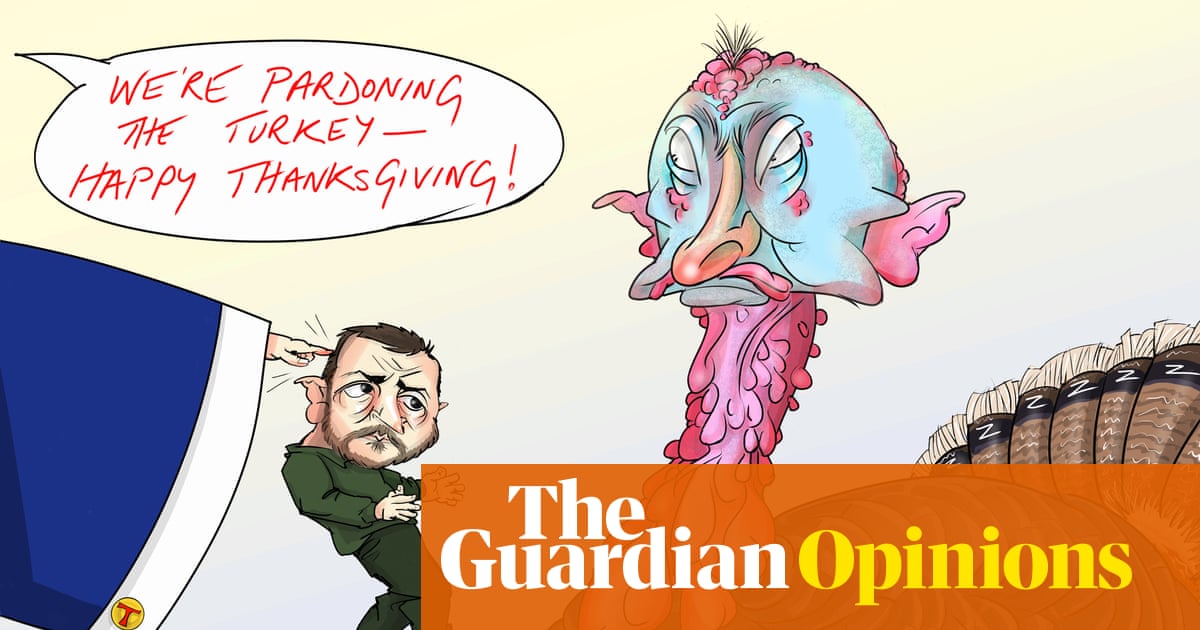

Not any more. Illiberal populism has spread across the world, either challenging for power or entrenching itself in office, from Argentina to Italy, France to Indonesia, Hungary to Britain. But probably the most significant example of a relatively free, pluralist society and political system turning into something very different remains the US, now nine months into Donald Trump’s second term.

As it often does, the US is demonstrating what the future could be for much of the world. Trump’s purges of immigrants, centralisation of power, suppression of dissent, rewarding of loyal oligarchs and contempt for truth and the law are not unique. Even governments which present themselves as alternatives to populism, such as Keir Starmer’s, increasingly share some of its features, such as a performative severity towards asylum seekers. Yet with over three years left of Trump’s frenetic presidency, and possibly more – were he to overcome the constitutional and electoral obstacles to a third term – life under him already provides the most unsettling picture of democracy under siege so far.

Partly because populism is divisive – setting “the people” against their supposed enemies – and partly because Trump is so volatile, the domestic impact of his regime is very uneven. And so is how different groups and individuals respond to its actions. These complex, often disturbing patterns are particularly clear in California, one of the places he most dislikes, for its liberal values and multiculturalism, and where his regime has most aggressively intervened.

In Los Angeles, where US marines, national guard troops and armed officers of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) have been controversially deployed by the federal government on and off since June, some largely Latino neighbourhoods remain eerily quiet. In Boyle Heights last Wednesday morning, two of the usual hubs for shopping and socialising, Cesar Chavez Avenue and Mariachi Plaza, were almost deserted, bakeries and cafes empty, only a few of the square’s outdoor seats taken, despite a mellow autumn sun. Fear of sudden arrest, detention and deportation has kept many people indoors and away from public spaces for months.

Yet in the neighbouring arts district of downtown LA, a gentrified grid of former warehouses and factories, the bakeries and cafes were busy as usual. Over pricey iced coffees and fat, artisanal sandwiches, fashionably dressed clusters of largely white people chatted about their latest cultural projects. The fact that Trump and his supporters would probably hate the whole scene, or that something approaching martial law had been imposed just up the road, did not appear to be affecting these ambitious millennials. In the US, as in other countries that are becoming or have become authoritarian, for those spared by the state, careers, social lives, leisure and consumerism carry on – and sometimes with a new intensity, as a form of escape.

However, avoiding and engaging with politics are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Often, both impulses coexist in people, especially when faced with something as simultaneously provocative and exhausting as hard-right populism. Periods of passivity, of apparent acceptance of the status quo, alternate with an urge to act.

Photograph: Michael Nigro/Pacific Press/Shutterstock

A fortnight ago, I went to a No Kings protest in Beverly Hills, a Californian city much less associated with activism than deep wealth. I expected a small gathering of elite liberals; instead, there were a couple of thousand boisterous people, of all ages, marching back and forth for hours along the edge of a park, carrying witty anti-Trump placards and chanting, to the accompaniment of drummers and constant passing car horns. The chants were not that fluent, which suggested that the participants did not protest often, and so did their gleeful smiles, as if they were doing something unexpectedly enjoyable and naughty. The whole event was uplifting: politics coming alive for people, perhaps for the first time.

But authoritarianism can provoke more jaded reactions as well. In San Francisco, traditionally a more political place, while there have been big No Kings protests, I also encountered a contempt towards Trump and his circle, for their blatant self-interest, cartoonish bullying and vast exaggerations, which risked becoming an angry apathy: a belief that the regime was a malign fact of life, like a government in a totally corrupt state or the Soviet bloc. This response, like refusing to rise to Trump’s attention-seeking, can be understood and justified as a form of conscious disengagement and as a coping mechanism. Yet while liberals and leftists brood, his regime relentlessly moves on.

While I was in San Francisco, it was rumoured that he was about to send troops or federal agents to what he claimed was a failing city. Some people I spoke to there ridiculed the idea. They gestured towards the many beautiful streets, successful businesses, picturesque green spaces and extensive public transport – a quality of life which, while increasingly unaffordable for some, exceeds that of many Trump-supporting places.

after newsletter promotion

However, in countries dominated by autocratic populism and digital media, propaganda often defeats facts. Trump called off his San Francisco invasion, but the possibility of it remains, like a crude but effective TV cliffhanger. Creating a politics which can stand up to rightwing populism’s showmanship and drama in a sustained way is a project which has so far defeated Trump’s opponents, with the exception of isolated leftwingers such as Zohran Mamdani and Bernie Sanders.

If Reform UK wins power, as seems increasingly possible, then British liberals and leftists will face the same challenge. Nigel Farage could launch endless eye-catching policies from Downing Street, such as the Trump-style deconstruction and politicisation of Whitehall, which Reform promised this week. These policies may fail or disappoint, as Trump’s often have, but make the political weather nevertheless. Unless populism’s opponents create an equally relentless and compelling movement, and draw in more of those whom populism victimises and scares into silence, then this age of autocrats will carry on. As the US shows, sporadic resistance, contempt and avoidance are not enough.